DRIVE TIME WITH CHARLES LINDBERGH

By John Francis Krimsky

The summer of 1960 had arrived, and I was looking for jobs near my home in Connecticut. It had been my routine for several years, and the hay fields beckoned. My father had an apartment in New York City and was a weekend commuter to the country. He had mentioned that a friend had placed his son with Pan Am in New York as a summer intern. I raised my hand, very interested in a summer in the city.

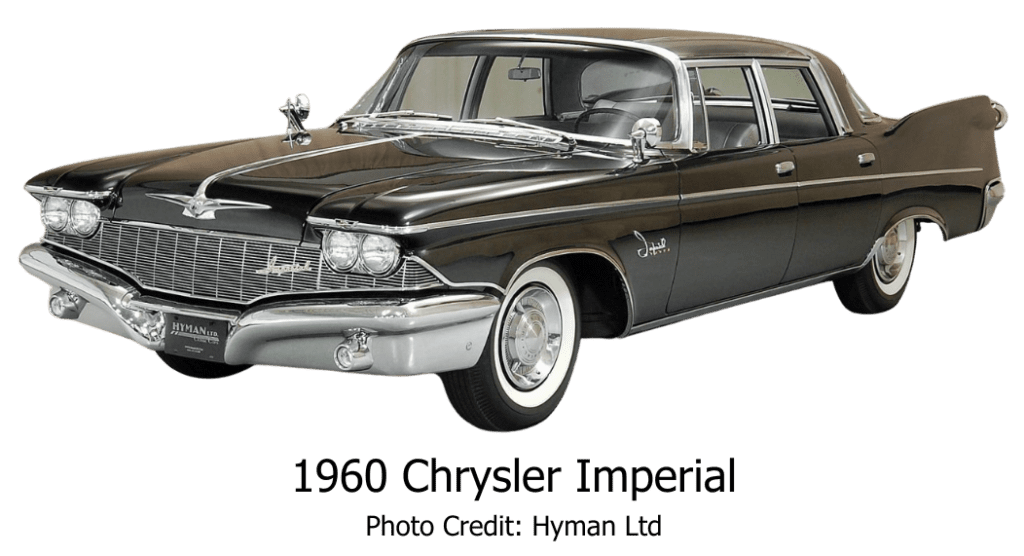

By June 1st, I was delivering mail to the Pan Am executives from the 72nd tower floor of the Chrysler Building. Since I was staying with my father in his 55th Street apartment close by, I was additionally tasked with arriving early at the Chrysler building, picking up the Pan Am limo, and proceeding to Chairman Juan Trippe’s apartment to pick him up for his ride to the office. Mr. Trippe was a member of the Chrysler Board, so we were assured of the latest vehicle. Of course, the regular driver and official chauffeur made sure that I hadn’t put any dents in his pride and joy or soiled his precious hat, which was stored untouched in the trunk. My headgear was a New York Yankees cap.

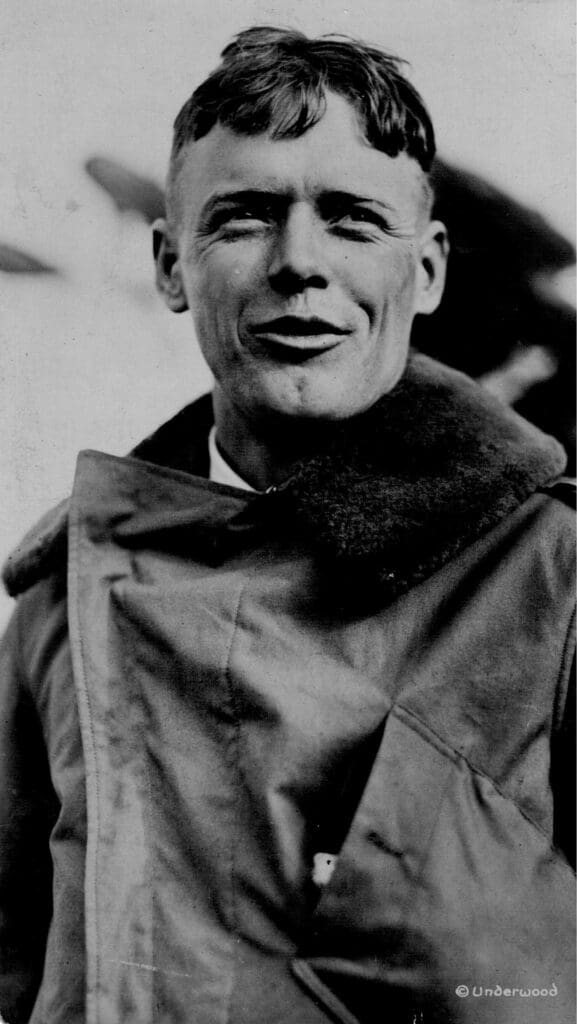

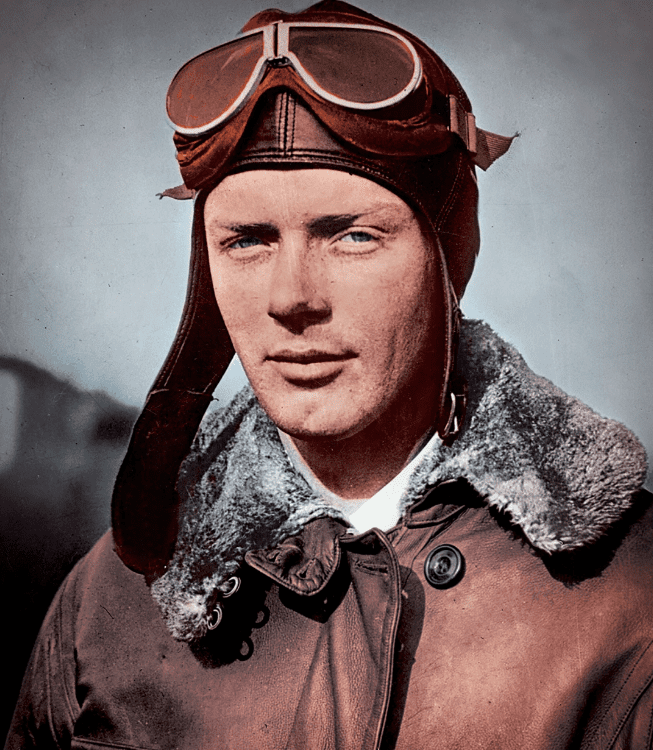

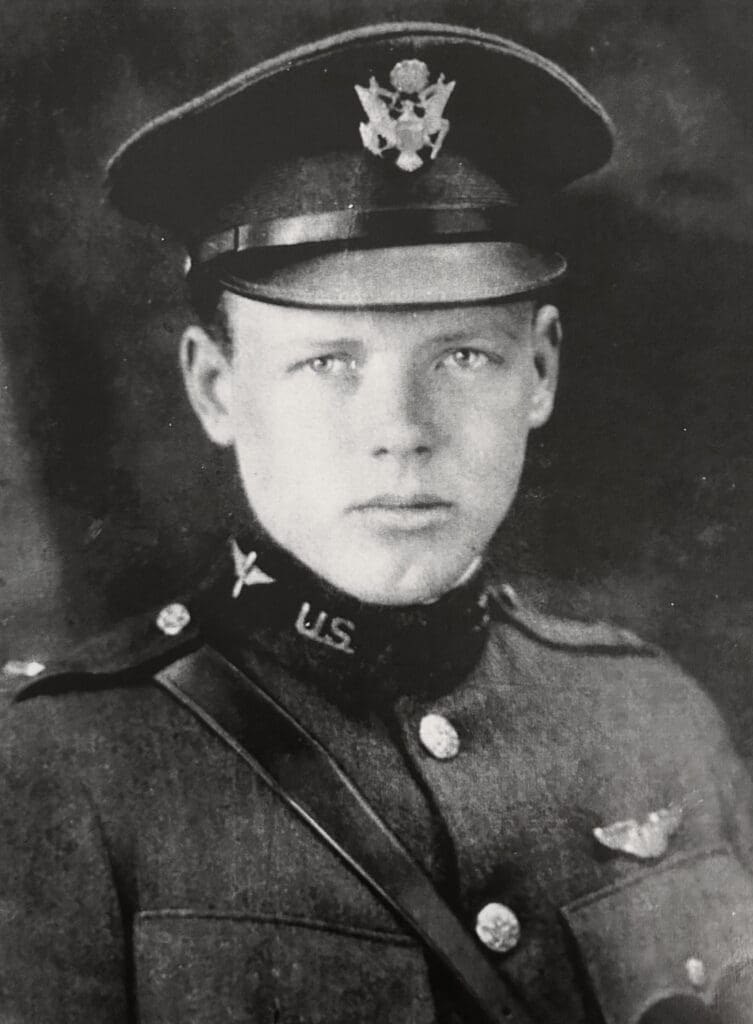

The high point of the summer came one morning when I was parked outside the Trippe apartment. I was startled by a knocking on the car’s rear window. I got out and found myself holding the door open for Charles Lindbergh. Lindbergh was in New York, serving as a special route advisor to Pan Am.

The Lone Eagle had orders from Anne Morrow Lindbergh, so I was directed to help find bookshops for items needed for her library. We commandeered Trippe’s car and went hunting all over the city. Lindbergh was very shy, so I would step in and negotiate autographs, so he avoided the chatter that went with the signing.

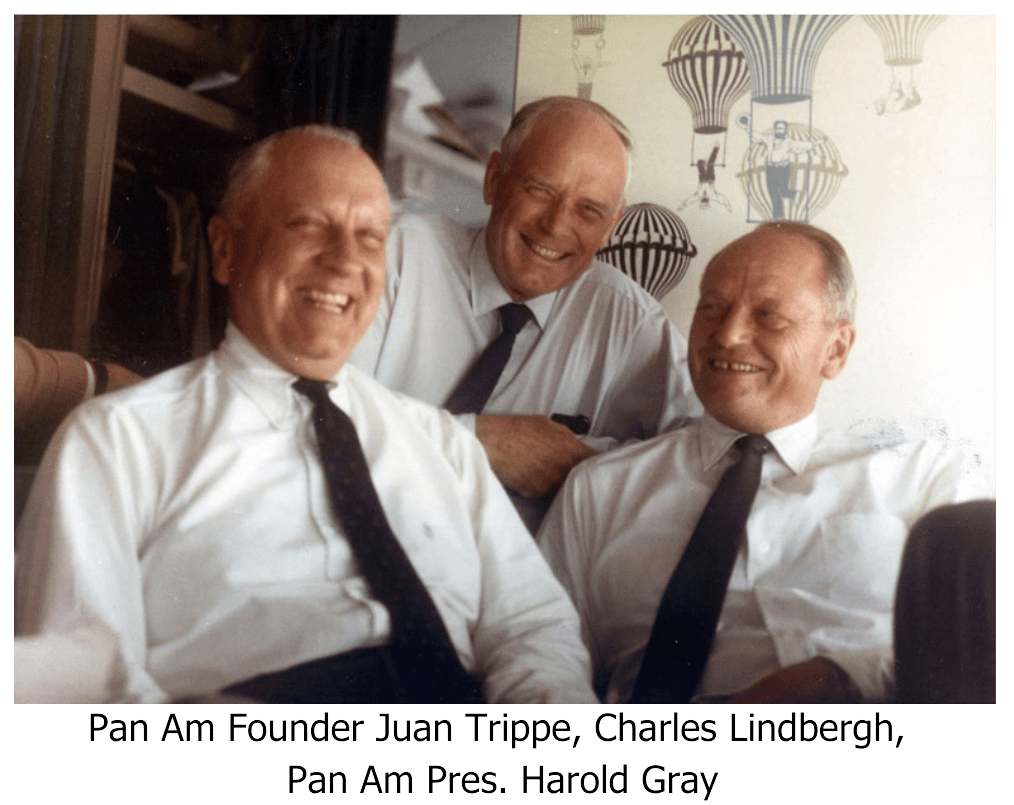

Lindbergh’s best friend in New York was Sam Pryor, a senior vice president at Pan Am. Pryor was vice chairman of the Republican National Committee and was instrumental in Pan Am’s strategic expansion of worldwide air services, often on routes surveyed by Lindbergh.

Pryor had supported Lindbergh since the Paris flight in 1927. They enjoyed each other and wanted to escape from corporate Pan Am at the Chrysler Building. I was given the keys to a flight line van from Idlewild and spent hours taking them to all sorts of interesting points. Their favorite was the flying boat Marine Air Terminal at LaGuardia, the site of the first transatlantic Pan Am Yankee Clipper flight in 1939 to Southampton, England. Lindbergh reminisced about flying the Boeing 314 on training flights. NBC Radio in New York reported that Lucky Lindy had been seen at the terminal, which ended those visits.

By 1970, I was in Osaka, Japan, as the director of Pan Am’s Pacific Wings Pavilion at EXPO’70 and honored to stand next to Lindbergh as he explained his aircraft and flight to the Japanese Royal Family. The Smithsonian had loaned the aircraft back to Lindbergh for the display but had a security detail on site to watch over it.

The plane was a single-engine Sirius that he and Anne Morrow had flown across Canada and the North Pacific to Japan in 1931. He showed us the flight logs and maps used while gathering firsthand information on possible trans-Pacific airline routes. Pryor had joined the group in Osaka, so it was quite a reunion at the Pan Am Clipper Club built especially for EXPO70.

Lindbergh and Pryor supported the Nature Conservancy’s efforts to preserve plants and wildlife in Kapahulu Valley in Hana, Hawaii. They had partnered to refurbish a small church at Hana, and Lindbergh was buried there in 1974, followed by Sam Pryor in 1985.

Lindbergh’s contributions to commercial aviation put the United States ahead of the rest and established Pan Am as the world’s leading airline. While Lucky Lindy had suffered controversies and the very sad loss of his child, what he did in the cockpit will be remembered as his major contribution to America’s air transport system. In 1954, President Eisenhower conveyed the rank of Brigadier General on Lindbergh for his many first flights on routes he surveyed, flew, and mapped around the world.

After leaving the Pan Am Mailroom, John F. Krimsky returned from a military leave of absence to eventually become a Pan Am overseas director in Asia, vice president of Advertising, Charters, Federal and Public Affairs, Pacific Marketing, and Senior Vice President and the Chief Marketing Officer for the carrier. He retired in 1986 to become Deputy Secretary General of the United States Olympic Committee.

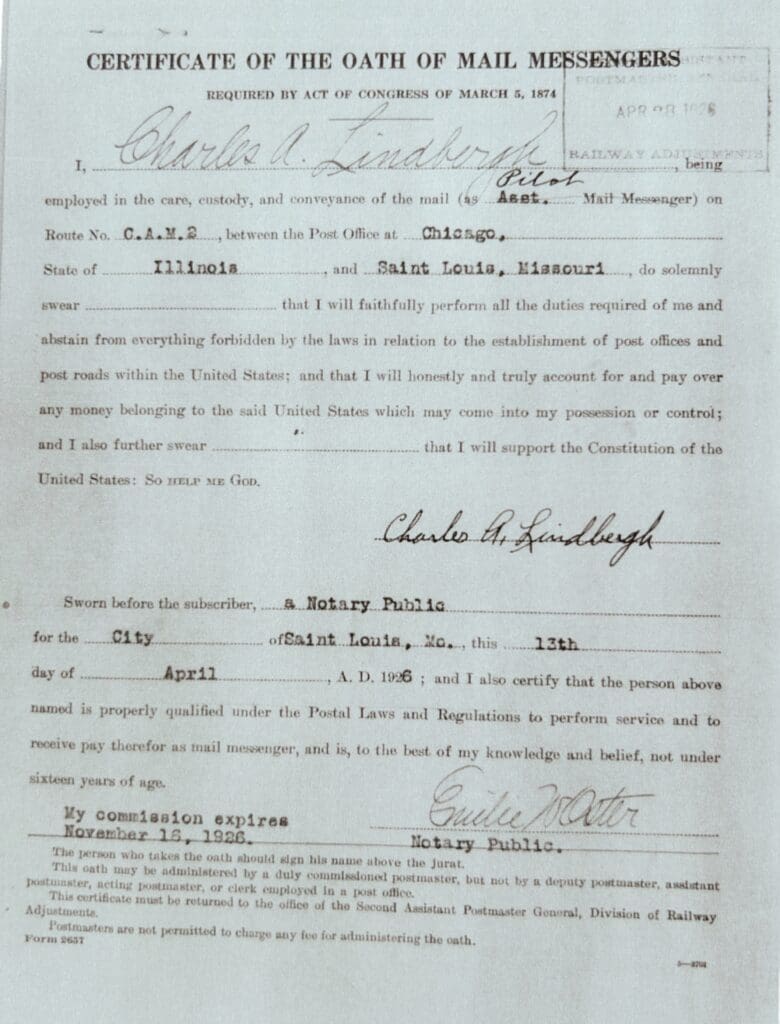

In 1989, the United States Postal Service recognized Krimsky’s preservation of Lindbergh’s historical record with Pan Am by giving him a copy of the certificate oath of mail pilot, signed by Lindbergh in 1926.